Traditional Languages Meet New Form of Self Expression

In this issue

Engage - Volume 7, Issue 2, Spring 2017

Engage - Volume 7, Issue 2, Spring 2017

The latest forms of digital communication and expression are breathing new life into traditional languages for many Indigenous youth.

Fransaskois artist, educator, activist, graphic designer, Zoé Fortier travelled throughout Saskatchewan ,including the Northern communities of La Ronge, Patuanak and Prince Albert, helping youth create ‘memes’ – a virally-transmitted cultural symbol or social idea. Fortier was hired as a SaskCulture Cultural Engagement Animateur (CEA) in 2016.

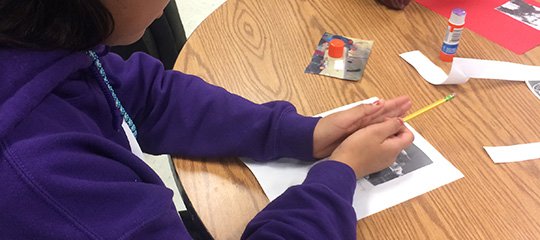

At her meme-making workshops in the North, Fortier encouraged her participants, many of them Indigenous youth, to construct memes in their traditional language (such as Cree or Dene) as a way of practicing and using their language skills. She based and designed her workshop on the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action.

Language teachers told Fortier they were inspired by the simple workshop idea she proposed. They found that the young participants discovered that their languages are alive and still part of the contemporary Saskatchewan cultural landscape.

“It felt extremely rewarding to reach out to youth and make them feel good about being ‘gifted’ with more than one language – or rather, of having a different perspective on life in Saskatchewan,” explains Fortier. “I think we are at the brink of a whole new wave of cultural programming that will be language-orientated.”

Fortier also believes that it is important to seek ways of encouraging Indigenous language retention by sharing ideas and resources on how youth can practice and use their language skills.

”First Nations people want to regain access to their languages, and they want to engage their youth with their languages,” she adds.

She also is happy that the memes produced by the youth are now housed online where they will remain accessible for all.

"First Nations people want to regain access to their languages, and they want to engage their youth with their languages."

The project also saw Fortier reflecting on her own youth. “I saw my younger self, struggling to feel confident in the fact that my language was not a barrier but the building blocks to who I was as a Saskatchewanite,” she explains. “The more they reject who they are to fit in, the more they feel that who they are or what they have to offer is ‘not good enough’ or ‘unwelcome’.” Fortier found the young people she worked with would reject who they were to fit in. “A lot of young people struggle to understand that being different means that they bring something new and unique to the world.”

Fortier says she believes the richness of human experience depends on our willingness to include and value different, and not so mainstream, perspectives and life experiences. “I was so happy that I could make some of these young people feel valued for all the different parts that formed them.”