Finding Your Family Roots

In this issue

Engage - Volume 7, Issue 1, Fall/Winter 2016

Engage - Volume 7, Issue 1, Fall/Winter 2016

Related Programs

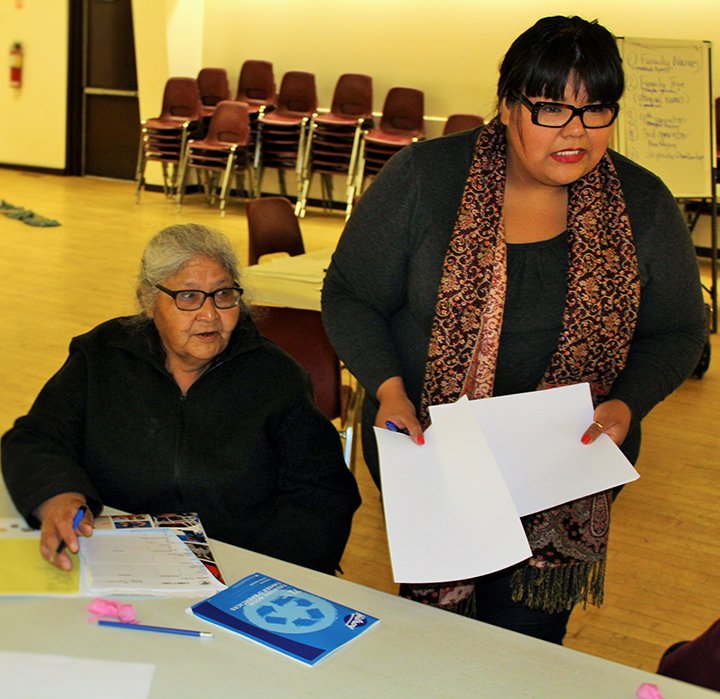

A new project is helping First Nations youth get in touch with their roots.

The Fishing Lake First Nation Genealogy Project, which emerged as a partnership between the Fishing Lake Youth Group and Fishing Lake First Nation, brought elders and youth together. According to Osawa Kiniw Kayseas, project coordinator, “Our main goal was to have the Elders in the community mentor and share their knowledge with the youth and assist with the genealogy project because they are the knowledge keepers in the community.”

Nora Kayseas, an Elder who was part of the Fishing Lake First Nation Genealogy Project, says, “It’s important for our people to know who we are and where we come from, also who we are related to. We need to be more proud of who we are. It was interesting, there were some things I didn’t know about, and I’m 70.”

Kayseas enjoyed the opportunity to learn and share the information with the generations that gathered for the sessions. It was important to meet face to face and to socialize as they did the project work, building trust as they listened to each other’s stories that were sometimes very difficult to hear. She explains how, “A boy about 14 years old said ‘Grandma, Kokum, how come you never told me this?’ And she said, ‘I tried but you weren’t listening’.”

Census data, other documents, and interviews with the Elders were collected as the group mapped family trees. “You would get the basic information but the stories threaded everything together,” says Osawa Kiniw Kayseas. Data collectors followed a set of standards to record consistent data and respected what people felt safe sharing. They had a workshop with the Saskatchewan Genealogy Society where they learned how to collect the data, write it down, and track it. They received advice about software and are still deciding which to use to keep and share their findings.

As they dug into archival material participants used magnifying glasses to decipher the century-old handwriting and the inconsistencies with spelling of the names and the ages of the people. Osawa Kiniw Kayseas was delighted to find that her grandmother’s traditional name as well as her English name was included in the Census. She was fascinated by the traditional names in the Old Nahkawe language.

“I think that was one of the most exciting parts of the whole process, we brought in a translator who spoke old Saulteaux and could translate the names into English.” She goes on to explain that the ceremonial language is complex and difficult to translate because a word can mean much more than one word, it can mean an entire paragraph explaining the idea behind it.

“The Elders are the last generation who are fluent speakers. Unless we revive our culture, unless we revive our language, there won’t be fluent speakers to carry on,” she explains.

Although the first official phase has been completed data collection continues and there is hope that the next phase will include the collection, scanning and cataloging of photographs belonging to the Elders. They also hope to visit museums housing Fishing Lake artifacts.

“There is no reason not to be proud of your history and who you are,” she says. “People always say ‘knowledge is power’, the reality is that knowledge is more than power, it can empower you. We want to empower our youth and the Elders.”

This project received funding from SaskCulture’s Aboriginal Arts and Culture Leadership Grant.